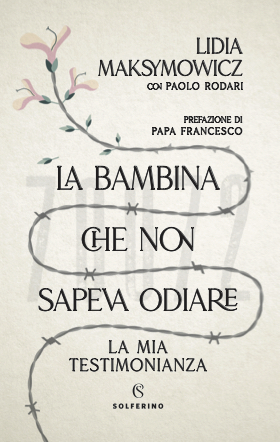

The Little Girl Who Could Not Hate

with Lidia Maksymowicz

Paolo Rodari

The heartbreaking, inspiring true story of a girl sent to Auschwitz who survived Mengele’s evil experiments. With a foreword by His Holiness Pope Francis.

At three years of age, Lidia Maksymowicz and her Catholic family were arrested and deported to Auschwitz from Belorussia, where they were hiding with Partisans. A survivor of Mengele’s experiments, she was adopted and raised by a Polish family who owned the land upon which Birkenau was built. At seven years of age, she had lost the ability to cry. In 1962, seventeen years after the liberation, she was reunited with both her mother and father who were living in Moscow. Thereafter, Lidia and her two mothers met up yearly in Auschwitz for the anniversary of its liberation.

Preface by Pope Francis:

To remember is an expression of humanity. Remembrance is a sign of civilization, a condition for a better future, one of peace and fraternity. My hope is that this book contributes to the remembrance of past events.

Remembrance also means being careful because these things can happen again, starting with ideological policies that are intended to save a people and end up destroying both them and humanity. Be aware of how this road of death, extermination, and brutality began.

When I met Lidia on May 26, 2021, in the courtyard of San Damaso, I kissed the arm upon which her number was tattooed in Auschwitz-Birkenau: 70072. It was a simple gesture of reconciliation aimed to keep the memory of the past alive. We, like Lidia, must learn from the darkest pages of history, so that they never repeat themselves, and we never again commit the same errors. And we must aim to work tirelessly to cultivate justice, build harmony and support integration. To be instruments of peace and the builders of a better world.

Vague images are all I remember. Like flashes that come and go in the night, lost in time, far away and yet close, very close, as though it were yesterday. Those are the memories that have been with me for as long as I can remember, since I was deported to the death camp with my mother.

I am three years old and she is twenty-two.

She is holding me as we cross the tracks of Birkenau. It is December of 1943, and the cold is unbearable. Snow falls like ice picks; the wind is like a whip; and all around us there is desolation. I can see the rust-colored wagon we arrived in – so many of us crammed together for days, not feeling our legs anymore, the constant sense of suffocating from one moment to the next. I am tempted to turn back and climb into the wagon. A moment ago, all I had wanted was to get out, breathe fresh air, but now, I wish to go back, go home.

I recall being embraced. My mother covers my face, or perhaps it is I who try to bury my face in her breasts which feel emptier, smaller, after days of seemingly infinite travel. The relentless train accelerated and then decelerated, making interminable stops in the foreign countryside.

Some of the German soldiers divide the new arrivals into two lines, other soldiers guard us from behind, and even more watch from a brick tower above. My mother and I are ordered to stand in the line on the right. The elderly, the fragile and the weak are ordered to the left. There are no clues to help interpret what is happening and what is still in store for us. No one has the energy to protest; any sort of rebellion would be useless anyway. We are so tired.

My mother and I stink. And everyone else from the train does too. And yet that smell is the only thing familiar, even friendly in this alien place. Where are we? No one speaks, no one explains. We are here and that is it.

Barking dogs. That is something I will never forget. Even today, when I hear a dog barking on the street, my mind takes me back to when I was standing in that line, suspended between the snow and the wind while soldiers shout in a foreign language. The SS (I would later learn who they were) return in my sleep, and in dreams they seem real. I awake in the middle of the night drenched in sweat, afraid and shaking. They yell at me although I cannot understand what they say, they spit and laugh with contempt. Their expression is full of hatred.

The animals are kept on a leash. They foam at the mouth, encouraged by the whips of the Germans who are entertained when they snarl at us, showing their teeth. The dogs that launch towards us do not realize that their prey has already surrendered. And some are dead.

My mother is forcefully torn from me, just as other mothers and children are. She screams and cries and disappears to someplace I don’t know. I see her shortly afterwards, or I think so, her hair shaved and completely naked. Without a single strand of hair on her head, she still takes me in her arms and hugs me, smiling. I remember that, her smiling as though she were saying: relax, it is all going to be fine. I ask her where her braids have gone, but she does not answer. I ask her where grandma and grandpa are, but she still doesn’t answer.

We see dark clouds of smoke coming from the other end of the camp. They contain the flames of the burning crematory. Soot covers the sky. I learned later that the Polish residents of the nearby towns, even further than Osweicim and Vistola, filled their lungs with that same soot and smelled that same stink of burning flesh infesting the camp. They understand just as we do. No one speaks. And my grandparents are no longer with us.

There is barbwire beyond the smokestacks. Beyond the barbwire, there are spare trees and beyond them, there is a clearing for as far as I can see. I want to be there, running towards freedom, as far away as possible. Freedom is so close, just a few meters over the fence, but unreachable. I am told that some people have tried to climb over the fence and they ended up electrocuted. Others were shot down after just a few steps.

Today I find it difficult to reconstruct what I went through. At over eighty years of age, I cannot honestly say if the flashes that pierce my memory like a sharp sword are my own experiences or a reconstruction of my experiences told to me by the other survivors, older ones, who were there with me at the time and made it out, like me. The only thing I can say for sure is that I was there. Perhaps my memories have become a collective experience that I am no longer able to distinguish from the stories. I can’t do anything about that, it is just the way it is.

I was very small when I first came to the camp and I was close to six years old when I left it. I am one of the children, perhaps even the youngest, who was able to live longest in the camps. Often, I ask myself why I can remember at all… that in and of itself is immensely disturbing to me. I am certainly unaware of all the abuse that I have been subject to and perhaps that is a blessing. One thing is for sure: thirteen months in Birkenau leave their mark on your soul at any age. Those days, months, and years damaged me and they will stay with me forever, until I die.

Birkenau is an indelible part of all those who were there. It is a monster that speaks of its experiences every day, in my smile and in my silence. It never dies. This is something that I realize after every speech I make, every discussion, telling people around the world what happened to me. Often, I surprise myself by mentioning something new, a detail that occurs to me at the time, like a memory that has floated to the surface. When my family tells me that they never heard that detail, I answer that it was inside me all the time, but only now found its way out. That is the way the child’s mind works; it holds memories inside like a warehouse. They may be hidden or confused but they are never forgotten. There is no such thing as burying a memory, it finds a way to unveil itself. Sometimes it takes years, but this is how I relive my past.

What was done to me during those long months of prison? My body experienced it, but my mind filed it away and buried it. But every year something surfaces, like relics tossed to shore by the sea. My spirit is like an ancient iceberg that is melting with time. The cold and horrors of Birkenau covered everything, not just memory: emotions, feelings and words. But the passing seasons have given way to mild weather and what was once covered is now, slowly, seeing the light.

My life’s objective is to come to terms with all of this. It is hard and painful, but I do it not just for myself. I retell my story for others – friends, strangers, for friends of friends that I do not know but who are part of an extended family – because they are fellow human beings. I want to be clear about what I believe: the darkness of the concentration camps is not done and finished with. The hatred that nourished those places lurks eternally. It is always ready to surface so we must be vigilant at all times by remembering what happened. How can we give meaning to the winters spent in the camp? To make people conscious of their darkest impulses, not to tolerate racism or hatred, and to encourage citizens to raise their voices. If we feed that positive energy into others, it will serve as a lymph that will save us.

I read about a new wave of antisemitism, hatred on the horizon. For those of us who survived the camps, antisemitism seems unimaginable and yet ever-present. Because for us it didn’t happen decades ago, it is a hell still alive within us, which seems like yesterday, or even hours ago. Since we only just managed to put it behind us, I imagine how easily it could return.

What was the error committed even before the camps existed? Allowing ordinary citizens to express an illogical hostility which suddenly became legitimatized. And it is still that way. We allow words that are filled with hatred, division and close-mindedness. Hearing politicians speak that way today here in Europe leaves me breathless. In moments like these we have the capacity to revert into darkness. Let’s not ever forget that.

My mother is a beautiful woman. On the train to hell, her long blond hair is gathered in two braids. She was strong, athletic, proud to be from Belorussia, descendent from the Eastern Slavic tribes. She was a Partisan who resisted every sort of invader, until the Nazis captured her at the end of 1943. Even in the camps she continued to fight, but her weapon was silence. In the forests of Belorussia, she spoke up, commanded, and organized defense teams. But in Birkenau, her struggle consisted of silence and indifference to her enemies. More important than anything else though, she learned to crawl.

There are only fifty meters (I later measured) between her barracks and mine, with a third barracks in the middle. When she visited me, every now and then, she ran huge risks. A German soldier with a weapon in his hands was stationed on a wooden tower nearby. He watched for moving targets and if he saw her crawling, he would either shoot her or call for her to be sent to the gas chambers. When she was sure that there was no danger and that she wouldn’t be seen, she did it anyway. In the dark, in grass or mud, she crawled, fearless.

I remember her hugging me during those visits. There was no food, but every now and then she somehow managed to smuggle me onions. She fed me with her bony fingers and then I ate alone in the dark. Sometimes I tasted the dirt, felt it between my teeth. There was no water to clean the onion, so I ate them as they came, without wasting even the tiniest bit. And I share with no one. As unattractive as it is, I admit that the instinct for survival guides me like no other. It is the same with the other children: a ferocious and brutal primal instinct. That is what we became and what we are; we share that trait in Birkenau.

I have little memory of our conversations and yet there must have been many. The only words that stand out in my memory are when I begged my mother to leave me her hands instead of onions so that they could hold me during the long, dark nights.

The nights in camp were terrible. I suffered from fear and the feeling of abandonment. I felt as though I would be lost there forever.

My mother’s hands are skinny and dirty, because she pulls herself along by groping at the ground. Sometimes she crawls in mud, her nails black with the wet earth beneath her. Meter after meter.

The children’s barracks where I sleep are reserved for Doctor Josef Mengele’s guinea pigs, us. Wooden shelves serve as beds and every compartment has three, one over the other along the entire rectangle perimeter of the barracks. We practically sleep on each other like ants. I learned early that it is better to stay on the top level, near the ceiling. That way you avoid the dripping excrement. I am not always able to find the sleeping place I want so sometimes I am forced to stay in the middle. Other times, on the lowest level. When that happens, I know what to expect but I accept it in silence. Complaining and crying is seen as a sign of weakness and in Birkenau you must stay strong. Resolute, but not arrogant, and alive.

My mother looks for me. She whispers my name.

Luda?

If no one answers, she moves on and asks again: Luda?

She usually has to look for me just to hold my hand, but at least she knows I am still there, and Doctor Mengele didn’t take me away or kill me while she was working in the fields. At least I was back in the barracks alive, hurt, but alive.

She slips on the brick pavement. The children’s barracks is the only one to have a floor. The walls are filled with drawings.

One day she came and couldn’t find me. I was nowhere to be seen, not on any of the wooden planks. They told her that Mengele had taken me the day before. She returned the next day, desperate, and still I was not there. The third day, she found me, unconscious, lying on a dirty slate, cold as glass. Mengele must have gone overboard that day.

My mother hugged me and kissed me, trying to help me regain consciousness. She can’t do much else. I wake up and survive, a miracle in days of death and desolation.

Thirteen months in Birkenau means two winters and the suffocating humidity of the continental European summer. In the Spring, even though flowers grow, fed by the ashes of the crematory, they don’t really bring hope. And the Autumn season feels like an end since it preannounces the cold of winter. There is no future in the seasons there.

I never asked my mother where the onions came from although later in life, I developed my own theory. My mother was a healthy young woman and every day she was taken out of the camp, beyond the fence and the crematory, to work along the river. Men and women were forced to repair the dams along the river, clear out the blockage, and cut the reeds that grow around it. The village of Harmeze, not far from there, was occupied by the Nazis who built a farm to raise poultry and produce food for the SS. Some prisoners were able to steal food from there, but I believe that my mother’s onions came from the generosity of Polish people who lived near the camp. She never really offered an explanation. Take it, she would say, and I answered without asking further.

As the war went on, my mother’s visits became increasingly rare. She wasn’t really able to be with me, to keep me company, because she was afraid of being found. But when she did come, and especially in the end, she forced me to repeat my name, my age and country. She made sure I would remember who I was and where I came from in case she didn’t survive the war. She wanted me to remember her, the woman who gave birth to me, who fed me and first held me so that I could one day find her again. She made me repeat it: my name is Ljudmila, Luda, I am five years old and I come from Belorussia, near Vitebsk on the border with Poland. She promised that sooner or later she would take me with her, that this would all end soon and we would return home, to our village, our forest and our land where everything would be the same. But the days went on and nothing changed. We were lined up, divided into two lines, the longest line went to their deaths and a few of us survived. Those who rebelled were executed.

We considered the Germans animals. Sometimes we would have to stand naked in front of them. They didn’t know that we felt no shame because you can’t feel shame in front of animals. Nude or dressed, it was the same for us children.

When my mother returns to her barracks, I close up like a porcupine and return to my world made of silence, my own, which is the only answer I could offer my tormentors. With no teachers, friends, or allies to teach me, I depended on my instinct. When a mouse crawled on top of me in search of food, I remained silent; when the child next to me coughed in the night and died; when the lice and ticks attacked me; when the SS came to take me to Mengele. In that silence, I tried to disappear so that I wouldn’t die. It is a silent front for my mother who forces herself to seem calm. I do not want to seem weak in her eyes. I don’t want to make her suffer and I don’t want myself to suffer either.

Corriere della Sera – Lidia, bambina ad Auschwitz: i ricordi di una sopravvissuta

Che tempo che fa 23/01/2022 – Interview to Lidia Maksymowicz

Rights sold:

Brazil (Companhia das letras)

Croatia (Skorpion)

Czech Republic (Dobrovsky)

France (Michel Lafon)

Germany (Heyne)

Hungary (Alexandra Group)

Netherlands (Mozaiek)

Poland (Wydawniczy Znak)

Portugal (Porto)

Romania (Bookzone)

Russia (Eksmo)

Slovakia (Citadella Publishing)

Spain (Roca Editorial)

UK (Pan Macmillan WE)