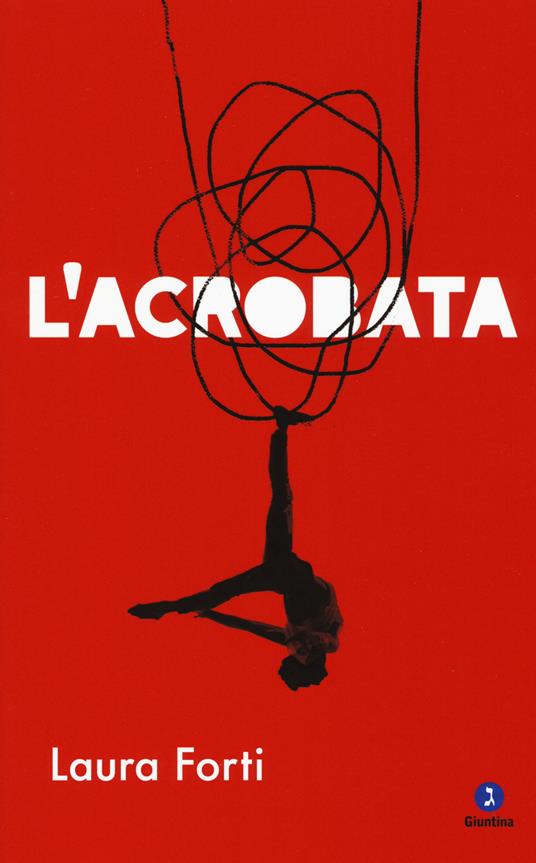

The Acrobat

Laura Forti

A family saga of four generations of Jews in the diaspora.

From her house in Sweden, an elderly scientist, addresses her grandson who knows little of his family: “We were like seeds in the wind, an ever -changing wind, and we never knew where we would land. We Jews had to live lightly, ready to flee when the wind changed direction.”

At the center of the story is José Valenzuela Levi, the boy’s father who ultimately returned to Chile and died trying to overthrow Pinochet. In this complex confession, filled with heartbreaking emotion, the elderly protagonist finds herself alone, guilty of having given her son “a thirst for justice and the language of rebellion.”

The narration, based on the authors family story, takes us from anger to guilt and ultimately ends with reconciliation.

Letter from the author

When I wrote The Acrobat, I felt like I was completing a mission that lasted many years. It all started with a business trip I made to Santiago in 2008. I knew it would not be painless, because after the racial laws that tore us apart in 1938, some members of my family had fled to Chile. Others remained in Italy, confident that those laws were nothing more than a temporary measure. So my family, which had already fled Russia during the Tsar’s anti-Jewish persecution, now found itself under a new dictatorship, that of Mussolini. In the years following, we received only vague and confused news of those who had chosen exile in another continent. We knew that they were Communists, that they had embraced the values of Salvador Allende and that after the unsuccessful coup, they were forced to escape once again. During their flight from South America to Europe, I met a cousin of my mother’s and her sixteen year old son, Pepo who was much older than me. They stopped at our house on their way to Sweden which had offered them refuge. Pepo played the guitar, recited poems by Pablo Neruda, and entertained me with coin tricks. I was probably a little in love with him, because for years, I kept his photo hidden in a dresser drawer. He was my prince, my handsome hero. Some time passed and we lost track of them until the news came that my cousin Pepo had been killed by the police in Chile. We believed he must have been one of the many dissident students murdered under Pinochet’s regime. The news was shrouded by a familiar silence, cold as a tombstone, which often accompanies family secrets. I only remember that, from that moment on, I saw the boy’s photograph in a new light. It was the photo of a dead man, and I felt that somehow I had become its keeper. That is why the trip to Santiago was important to me. When I arrived there, I began to ask questions about the dictatorship and often met great reticence. I looked for answers in books and old papers and finally, on the internet, where I made a shocking discovery. That young man, who I affectionately called Pepo, was actually Jose Valenzuela Levi, the mastermind of the 1986 assassination attempt of Pinochet. He was killed a year later in a demonstrative massacre, the Matanza de orpus Christi, along with his companions. Pep/José was twenty nine years old.

I was surprised, but also angry. How could I know nothing of this tragic story and the important political past of a cousin of mine? Why had my family removed or censored his memory?

This discovery gave birth to a long period of historical research, which led me to write various texts, to renew relationships, to interview others and to elaborate the feelings connected with family exile, at the basis of so many choices and intimate decisions. Ultimately, from this complex and dense material, a voice emerged: that of a mother who has lost a child. An elderly woman tells her grandson – who has not lived through the regime and knows nothing of his family- about his father, a young revolutionary who sacrificed his life for an ideal. But it is not easy for her write an email, a means which is foreign to her. The experience is excruciating. It reopens a wound that hides ambivalence and guilt, and forces her to finally mourn in the cold of Sweden. But what choice does she have? Without memory, how can her grandson form his own identity, appropriate his past and know his history?

The newborn story leaps and stumbles in a progressive nearing to raw emotion, a countdown towards the inexorable ending: the merciless analysis of a woman who raised a child with the values of freedom and justice, only to watch him be torn apart and die by virtue of these same ideals. A mother who is terribly proud, but perhaps would have preferred a normal, indifferent son “who might be stupid but still alive”.

The novel is called The Acrobat not only because the grandson to whom the letters are sent works in a circus, but because it is a metaphor for exile which tears families apart, upsetting the existence of all the characters. Like their Patriarch Juliusz, who cut ties with a Russia enflamed by pogroms and exiled to Europe with nothing but a suitcase. Like the narrator, Pepo’s mother, having left Fascist Italy for Chile, and then Chile for Sweden, precariously balanced between present and memory. Yet Pepo breaks this long chain of exile, when he returns home to fight for freedom, and to correct the evil and loss of his own country. Through his silence, Pepo’s son, invisibly present in the book, accompanies his grandmother on her voyage down memory lane, where she breaks her wall of silence and finally tells her story which is all of their stories: a painful testament of love that will allow them both to find meaning in loss.